Multiplicative Processes in Finance and Insurance

🎯 Why This Matters

Multiplicative processes reveal why volatility is costly even when expected returns are unchanged: the volatility drag effect means a 30% volatility with 10% average return underperforms a steady 10% return due to compounding asymmetry. For P&C actuaries, this framework transforms how we value insurance: beyond covering expected losses, insurance creates value by reducing volatility drag, enabling higher sustainable growth rates. The Kelly criterion provides the mathematical foundation for optimal retention decisions, showing that maximizing log-wealth growth naturally prevents ruin while optimizing long-term performance. Path dependence explains why claims history, experience rating, and capital requirements can't be reduced to simple point estimates; the entire trajectory matters. These mathematics prove that smooth, predictable cash flows are inherently more valuable than volatile ones with the same mean, justifying insurance premiums that exceed expected losses and explaining why diversification and reinsurance remain rational even when they reduce expected returns.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Multiplicative Dynamics

Definition

A multiplicative process is one where changes are proportional to the current state:

where \(R_t\) is a random growth factor. This contrasts with additive processes:

where \(A_t\) is a random increment.

Why Multiplicative Processes Matter

Most economic quantities evolve multiplicatively:

Wealth: Returns compound on existing capital

Populations: Growth rates apply to current size

Company revenues: Growth percentages, not fixed amounts

Insurance losses: Often proportional to exposure

Key Properties

Non-negative: Cannot go below zero (natural boundary)

Scale-dependent: Absolute changes depend on current level

Compound effects: Small differences accumulate exponentially

Log-additivity: Logarithms transform to additive process

Geometric Brownian Motion

Mathematical Definition

Geometric Brownian Motion (GBM) is the continuous-time limit of multiplicative random walks:

\(S_t\) = Stock price or wealth at time \(t\)

\(\mu\) = Drift parameter (expected return)

\(\sigma\) = Volatility parameter

\(W_t\) = Standard Brownian motion

Analytical Solution

The solution to the GBM stochastic differential equation is:

This shows explicitly the volatility drag term \(-\sigma^2/2\).

Properties of GBM

Log-normality: \(\ln(S_t/S_0)\) is normally distributed

Martingale property: Under risk-neutral measure with \(\mu = r\) (risk-free rate)

Self-similarity: Statistical properties scale with time

Markov property: Future depends only on present, not past

Simulation in Discrete Time

Euler-Maruyama discretization for time step \(\Delta t\):

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

def simulate_gbm(S0, mu, sigma, T, dt, n_paths=1000):

"""Simulate Geometric Brownian Motion paths."""

n_steps = int(T / dt)

t = np.linspace(0, T, n_steps + 1)

# Generate random shocks

dW = np.random.randn(n_paths, n_steps) * np.sqrt(dt)

# Initialize paths

S = np.zeros((n_paths, n_steps + 1))

S[:, 0] = S0

# Simulate using exact solution for each step

for i in range(n_steps):

S[:, i + 1] = S[:, i] * np.exp((mu - 0.5 * sigma**2) * dt + sigma * dW[:, i])

return t, S

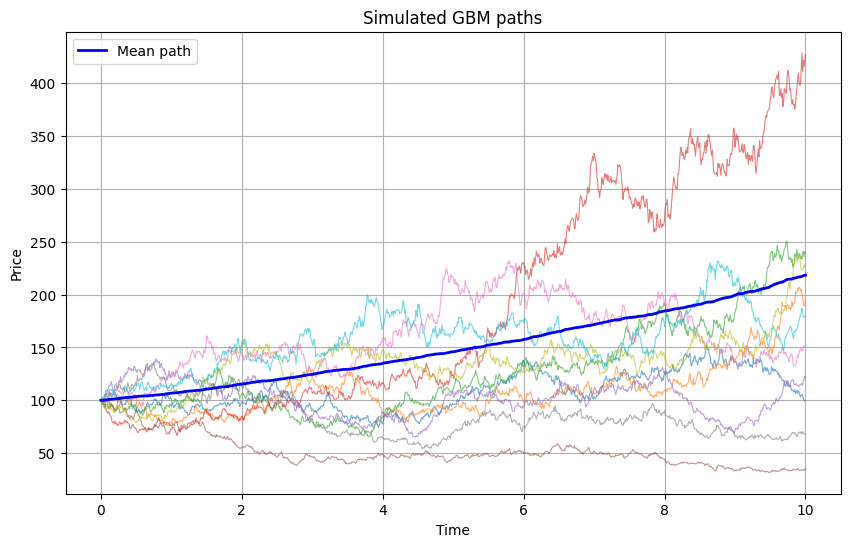

# Example simulation

t, paths = simulate_gbm(S0=100, mu=0.08, sigma=0.2, T=10, dt=0.01)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

n_plot = min(10, paths.shape[0]) # plot up to 100 paths for readability

plt.plot(t, paths[:n_plot].T, lw=0.8, alpha=0.6)

plt.plot(t, paths.mean(axis=0), color='blue', lw=2, label='Mean path')

plt.xlabel('Time')

plt.ylabel('Price')

plt.title('Simulated GBM paths')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

# Calculate statistics

final_values = paths[:, -1]

print(f"Mean final value: {np.mean(final_values):.2f}")

print(f"Median final value: {np.median(final_values):.2f}")

print(f"Probability of loss: {np.mean(final_values < 100):.1%}")

Sample Output

Mean final value: 218.46

Median final value: 178.65

Probability of loss: 18.3%

Log-Normal Distributions

Definition and Properties

If \(X \sim \text{LogNormal}(\mu, \sigma^2)\), then \(\ln(X) \sim \text{Normal}(\mu, \sigma^2)\).

Probability density function:

Moments of Log-Normal Distribution

For \(X \sim \text{LogNormal}(\mu, \sigma^2)\):

Mean: \(E[X] = e^{\mu + \sigma^2/2}\)

Median: \(\text{Med}[X] = e^{\mu}\)

Mode: \(\text{Mode}[X] = e^{\mu - \sigma^2}\)

Variance: \(\text{Var}[X] = e^{2\mu + \sigma^2}(e^{\sigma^2} - 1)\)

Note: Mean > Median > Mode (right-skewed distribution)

Connection to Multiplicative Processes

If returns are multiplicative with log-normal distribution:

Then wealth after \(n\) periods:

Taking logarithms:

By Central Limit Theorem, \(\ln(W_n)\) approaches normal distribution.

Insurance Loss Modeling

Log-normal distributions are common for:

Claim severities: Natural for multiplicative effects

Asset values: Result of compound growth

Time-to-event: With log-time normally distributed

from scipy import stats

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

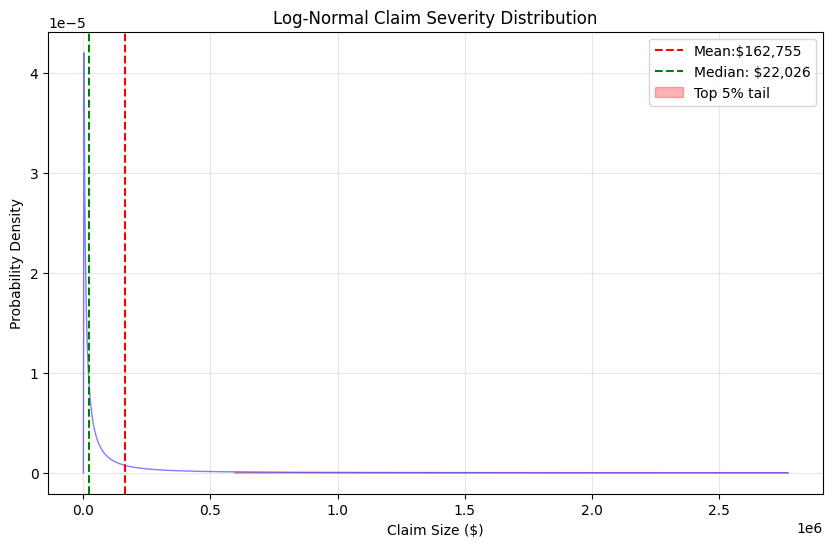

# Parameters for claim severity

mu_claim = 10 # log-mean (corresponds to ~$22k median)

sigma_claim = 2 # log-standard deviation

# Create distribution

claim_dist = stats.lognorm(s=sigma_claim, scale=np.exp(mu_claim))

# Calculate statistics

mean_claim = claim_dist.mean()

median_claim = claim_dist.median()

percentile_95 = claim_dist.ppf(0.95)

percentile_99 = claim_dist.ppf(0.99)

print(f"Mean claim:${mean_claim:,.0f}")

print(f"Median claim: ${median_claim:,.0f}")

print(f"95th percentile:${percentile_95:,.0f}")

print(f"99th percentile: ${percentile_99:,.0f}")

# Visualize

x = np.linspace(0, percentile_99 * 1.2, 1000)

pdf = claim_dist.pdf(x)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(x, pdf, 'b-', linewidth=2)

plt.axvline(mean_claim, color='r', linestyle='--', label=f'Mean:${mean_claim:,.0f}')

plt.axvline(median_claim,

color='g',

linestyle='--',

label=f'Median: ${median_claim:,.0f}')

plt.fill_between(x[x > percentile_95],

pdf[x > percentile_95],

alpha=0.3,

color='red',

label='Top 5% tail')

plt.xlabel('Claim Size ($)')

plt.ylabel('Probability Density')

plt.title('Log-Normal Claim Severity Distribution')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

Sample Output

Mean claim:$162,755

Median claim: $22,026

95th percentile:$591,080

99th percentile: $2,309,856

Path Dependence and History

Definition of Path Dependence

A process is path-dependent if the outcome depends not just on the starting and ending points, but on the entire trajectory taken.

Examples in Finance

Bankruptcy: Once wealth hits zero, it stays there

Credit ratings: History of defaults affects future borrowing

Barrier options: Payoff depends on whether price crossed a threshold

Asian options: Payoff based on average price over time

Mathematical Formulation

For a path-dependent functional:

Cannot be reduced to:

Impact on Insurance

Path dependence affects:

Claims development: Past payments influence reserves

Experience rating: History determines future premiums

Reputation effects: Past performance affects market position

Capital requirements: Regulatory views based on history

Measuring Path Dependence

# First run the GMB example above to generate `paths`

def calculate_path_metrics(paths):

"""Calculate various path-dependent metrics."""

metrics = {

'final_value': paths[:, -1],

'maximum': np.max(paths, axis=1),

'minimum': np.min(paths, axis=1),

'average': np.mean(paths, axis=1),

'max_drawdown': np.zeros(len(paths)),

'time_underwater': np.zeros(len(paths)),

'volatility_realized': np.zeros(len(paths))

}

for i, path in enumerate(paths):

# Maximum drawdown

cummax = np.maximum.accumulate(path)

drawdown = (cummax - path) / cummax

metrics['max_drawdown'][i] = np.max(drawdown)

# Time underwater

metrics['time_underwater'][i] = np.mean(path < path[0])

# Realized volatility

returns = np.diff(np.log(path))

metrics['volatility_realized'][i] = np.std(returns) * np.sqrt(252)

return metrics

# Analyze path dependence

metrics = calculate_path_metrics(paths)

# Compare final values with path metrics

correlation_matrix = np.corrcoef([

metrics['final_value'],

metrics['maximum'],

metrics['max_drawdown'],

metrics['volatility_realized']

])

print("Correlation with final value:")

print(f"Maximum reached: {correlation_matrix[0, 1]:.3f}")

print(f"Max drawdown: {correlation_matrix[0, 2]:.3f}")

print(f"Realized volatility: {correlation_matrix[0, 3]:.3f}")

Sample Output

Correlation with final value:

Maximum reached: 0.962

Max drawdown: -0.604

Realized volatility: -0.001

Growth Rate Calculations

Suppose we have a multiplicative process:

Where \(R_t\) is a random growth factor at each period with expectation \(R\).

Two Different Questions We Can Ask:

1. Ensemble Average (Arithmetic Mean):

“What is the expected wealth across many people/paths at time \(T\)?”

Person 1: \(W_T^{(1)} = W_0 \cdot R_1^{(1)} \cdot R_2^{(1)} \cdot ... \cdot R_T^{(1)}\)

Person 2: \(W_T^{(2)} = W_0 \cdot R_1^{(2)} \cdot R_2^{(2)} \cdot ... \cdot R_T^{(2)}\)

…

Person N: \(W_T^{(N)} = W_0 \cdot R_1^{(N)} \cdot R_2^{(N)} \cdot ... \cdot R_T^{(N)}\)

The ensemble average is the expected value: \(E[W_T]_\text{ensemble} = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^N{W_T^{(i)}}\)

As \(N \rightarrow \infin\), this converges to \(E[W_T] = W_0 \cdot E[R]^T\) (for i.i.d. returns).

And we have \(E[R] = 1 + r_a\)

2. Time Average (Geometric Mean):

“What growth rate does a single individual experience over time?”

For one specific path: \(W_T = W_0 \cdot R_1 \cdot R_2 \cdot ... \cdot R_T\)

The growth rate thus experienced is: \(g = (\frac{W_T}{W_0})^\frac{1}{T} - 1 = (\prod{R_t})^\frac{1}{T} - 1\)

As \(T \rightarrow \infin\), this converges to \(\langle g \rangle_\text{time} = \lim_{T \rightarrow \infin}{\frac{1}{T}\ln{\frac{W_T^{(i)}}{W_0}}} = E[\ln(R)]\)

And we have \(W_T = W_0 \cdot (1 + r_g)^T\)

Relationship Between Returns

For small returns, approximately:

Exact relationship:

Volatility Drag

The difference between arithmetic and geometric means:

This represents the cost of volatility on compound growth.

Example Calculation

def analyze_growth_rates(returns):

"""Compare different growth rate measures."""

# Arithmetic mean

r_arithmetic = np.mean(returns)

# Geometric mean

wealth_factor = np.prod(1 + returns)

r_geometric = wealth_factor**(1/len(returns)) - 1

# Log growth rate

log_returns = np.log(1 + returns)

g_log = np.mean(log_returns)

# Volatility

volatility = np.std(returns)

# Theoretical drag

theoretical_drag = volatility**2 / 2

actual_drag = r_arithmetic - r_geometric

results = {

'Arithmetic Mean': r_arithmetic,

'Geometric Mean': r_geometric,

'Log Growth Rate': g_log,

'Volatility': volatility,

'Theoretical Drag': theoretical_drag,

'Actual Drag': actual_drag,

'Final Wealth Multiple': wealth_factor

}

return results

# Example with volatile returns

np.random.seed(42)

returns = np.random.randn(100) * 0.3 + 0.1

# 10% mean, 30% volatility

results = analyze_growth_rates(returns)

for key, value in results.items():

if 'Wealth' in key:

print(f"{key}: {value:.2f}x")

else:

print(f"{key}: {value:.2%}")

Sample Output

Arithmetic Mean: 6.88%

Geometric Mean: 2.97%

Log Growth Rate: 2.92%

Volatility: 27.11%

Theoretical Drag: 3.67%

Actual Drag: 3.92%

Final Wealth Multiple: 18.62x

The Kelly Criterion

What Is It?

The Kelly Criterion is a mathematical framework that answers a critical question: “How much risk is too much?”

Originally developed for gambling and investing, it determines the optimal size of bets (or in insurance terms, retentions) to maximize long-term growth while avoiding ruin.

The formula balances two competing forces:

Too much risk retention → Higher probability of catastrophic loss

Too much risk transfer → Excessive premiums erode profitability

Kelly identifies the sweet spot that maximizes compound growth rate over time, not just expected value in any single period. In essence, Kelly solves a specific problem in situations where Ergodicity breaks down (when time ≠ ensemble averages).

Original Formulation

For a binary bet with probability \(p\) of winning \(b\) times the wager:

where \(f^*\) is the optimal fraction of wealth to bet.

Continuous Distribution

For continuous returns \(R\) with distribution \(F\):

Where the \(\arg\max\limits_f\) function returns \(f\) that maximizes the expectation.

Insurance Application

Optimal retention level:

Properties of Kelly Betting

Maximizes geometric growth: Optimal for long-term wealth

Never risks ruin: Always maintains positive wealth

Volatility-adjusted: Naturally accounts for risk

Time-consistent: Optimal regardless of horizon

Fractional Kelly

Due to estimation error and preferences, practitioners often use fractional Kelly:

where \(\alpha \in (0, 1]\), typically \(\alpha \approx\) 0.25 to 0.5.

Implementation

from scipy.optimize import minimize_scalar

def kelly_optimal_insurance(wealth, growth_rate, volatility,

claim_frequency, claim_severity_dist,

premium_loading=1.3):

"""Find Kelly-optimal insurance retention."""

def expected_log_wealth(retention):

# Annual premium

expected_loss = claim_frequency * claim_severity_dist.mean()

premium = min(expected_loss, retention) * premium_loading

# Simulate one year

n_sims = 10_000

final_wealth = np.zeros(n_sims)

for i in range(n_sims):

# Base growth

w = wealth * np.exp(growth_rate - 0.5*volatility**2 + volatility*np.random.randn())

# Claims

n_claims = np.random.poisson(claim_frequency)

if n_claims > 0:

claims = claim_severity_dist.rvs(n_claims)

total_claim = np.sum(claims)

retained_loss = min(total_claim, retention)

else:

retained_loss = 0

# Final wealth

final_wealth[i] = max(0, w - premium - retained_loss)

# Expected log wealth (excluding zeros)

positive_wealth = final_wealth[final_wealth > 0]

if len(positive_wealth) == 0:

return -np.inf

return np.mean(np.log(positive_wealth / wealth))

# Optimize

result = minimize_scalar(

lambda r: -expected_log_wealth(r),

bounds=(0, wealth * 0.5),

method='bounded'

)

return result.x

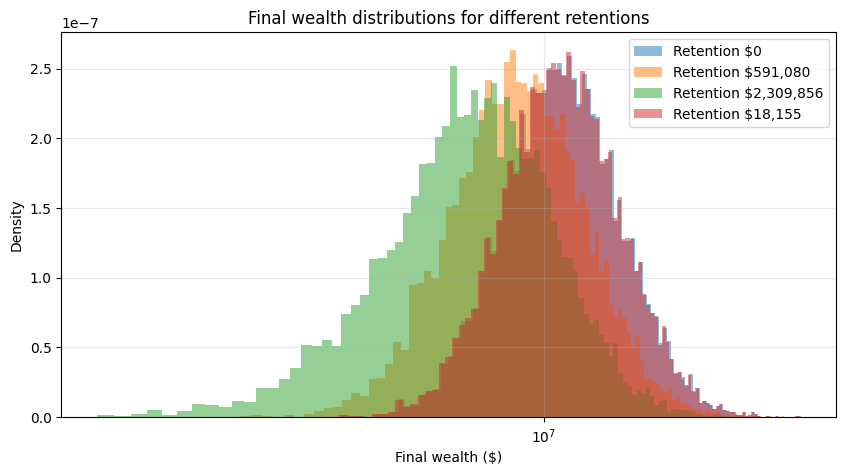

# Example usage

claim_dist = stats.lognorm(s=2, scale=50000)

optimal_retention = kelly_optimal_insurance(

wealth=10_000_000,

growth_rate=0.08,

volatility=0.15,

claim_frequency=3,

claim_severity_dist=claim_dist

)

print(f"Kelly-optimal retention: ${optimal_retention:,.0f}")

Sample Output

Kelly-optimal retention: $18,155

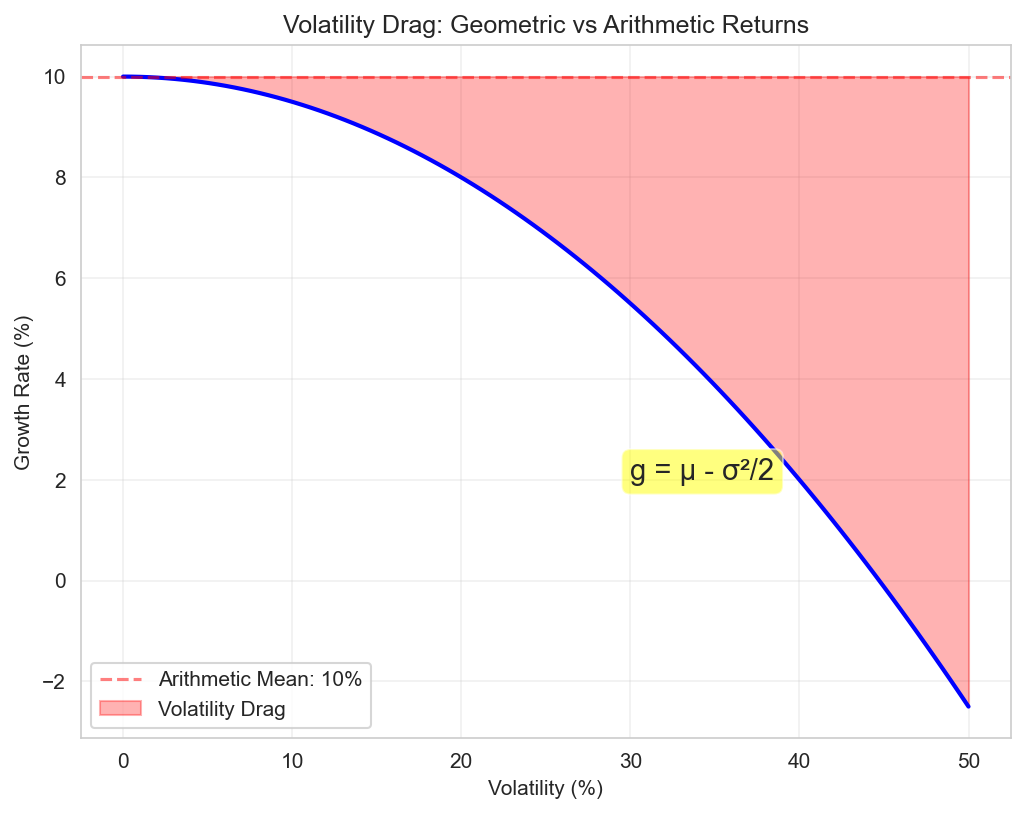

Volatility Drag

Figure: The impact of volatility on growth rates, showing how geometric mean decreases with volatility even when arithmetic mean is constant.

Mathematical Definition

For a process with arithmetic mean return \(\mu\) and volatility \(\sigma\):

This reduces the geometric growth rate:

Intuitive Explanation

Consider two scenarios:

Steady 10% annual return → \(1.1^{10} = 2.594x\) after 10 years

Alternating +30% and -10% (average 10%) → \((1.3 × 0.9)^5 = 2.373x\)

The volatile path underperforms despite the same average.

Impact on Insurance Decisions

Insurance reduces volatility drag by:

Capping downside losses

Smoothing cash flows

Enabling higher risk-taking in core business

Quantifying the Benefit

def calculate_volatility_drag_benefit(base_volatility,

volatility_with_insurance,

time_horizon=10):

"""Calculate wealth improvement from volatility reduction."""

# Assume same arithmetic mean

mu = 0.10

# Growth rates

g_without = mu - base_volatility**2 / 2

g_with = mu - volatility_with_insurance**2 / 2

# Wealth multiples

wealth_without = np.exp(g_without * time_horizon)

wealth_with = np.exp(g_with * time_horizon)

# Benefit

benefit = (wealth_with / wealth_without - 1) * 100

print(f"Base volatility: {base_volatility:.1%}")

print(f"Volatility with insurance: {volatility_with_insurance:.1%}")

print(f"Growth without insurance: {g_without:.2%}")

print(f"Growth with insurance: {g_with:.2%}")

print(f"Wealth improvement: {benefit:.1f}%")

return benefit

# Example

benefit = calculate_volatility_drag_benefit(

base_volatility=0.30,

volatility_with_insurance=0.15,

time_horizon=20

)

Sample Output

Base volatility: 30.0%

Volatility with insurance: 15.0%

Growth without insurance: 5.50%

Growth with insurance: 8.88%

Wealth improvement: 96.4%

Practical Examples

Example 1: Widget Manufacturer

A widget manufacturer faces:

$10M starting capital

Revenue growth: 8% expected, 15% volatility

Operating leverage: 2x (costs are 50% fixed)

Catastrophic risk: 5% chance to lose 50% of capital

def simulate_manufacturer(years=10, with_insurance=False):

"""Simulate manufacturer wealth evolution."""

W0 = 10_000_000 # \$10M initial capital

wealth = [W0]

for year in range(years):

# Revenue growth

revenue_shock = np.exp(0.08 - 0.5*0.15**2 + 0.15*np.random.randn())

# Operating leverage effect

profit_shock = 1 + 2 * (revenue_shock - 1)

# Catastrophic loss

cat_loss = wealth[-1] / 2.0

cat_prob = 0.05

if np.random.rand() < cat_prob:

loss = cat_loss

else:

loss = 0

if with_insurance:

retention = 500_000

premium = (cat_loss - retention) * cat_prob / 0.7 # 70% Loss Ratio

covered_loss = max(0, loss - retention)

net_loss = premium + min(loss, retention)

else:

net_loss = loss

# Update wealth

new_wealth = max(0, wealth[-1] * profit_shock - net_loss)

wealth.append(new_wealth)

return wealth

# Run simulations

np.random.seed(42)

n_sims = 100_000

results_with = []

results_without = []

for _ in range(n_sims):

results_with.append(simulate_manufacturer(20, True))

results_without.append(simulate_manufacturer(20, False))

# Analyze

final_with = [r[-1] for r in results_with]

final_without = [r[-1] for r in results_without]

fw = np.array(final_with)

fwo = np.array(final_without)

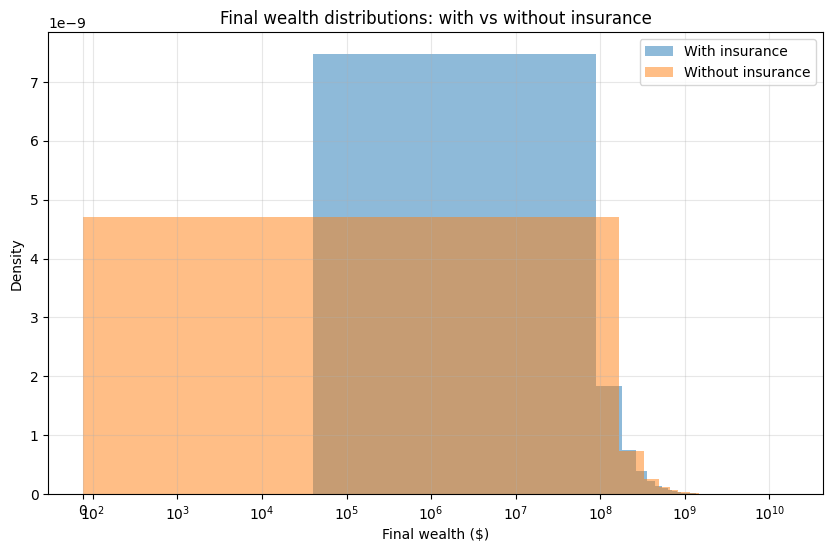

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.hist(fw, bins=100, density=True, alpha=0.5, label='With insurance')

plt.hist(fwo, bins=100, density=True, alpha=0.5, label='Without insurance')

plt.xscale('symlog', linthresh=1e3) # show tails but keep visibility near zero

plt.xlabel('Final wealth ($)')

plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.title('Final wealth distributions: with vs without insurance')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True, which='both', alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

print("With Insurance:")

print(f" Median final wealth: ${np.median(final_with):,.0f}")

print(f" Bankruptcy rate: {np.mean(np.array(final_with) == 0):.1%}")

print(f" Growth rate: {np.mean(np.log(np.array(final_with)[np.array(final_with) > 0] / 10_000_000) / 20):.2%}")

print("\nWithout Insurance:")

print(f" Median final wealth: ${np.median(final_without):,.0f}")

print(f" Bankruptcy rate: {np.mean(np.array(final_without) == 0):.1%}")

print(f" Growth rate: {np.mean(np.log(np.array(final_without)[np.array(final_without) > 0] / 10_000_000) / 20):.2%}")

Sample Output

With Insurance:

Median final wealth: $50,420,575

Bankruptcy rate: 0.0%

Growth rate: 7.98%

Without Insurance:

Median final wealth: $54,126,214

Bankruptcy rate: 0.9%

Growth rate: 8.09%

Example 2: Investment Portfolio

Portfolio with tail risk:

Starting portfolio of $100M

Fixed operating costs of $500K per year

Base Return: 7% with 15% Volatility

Tail event: 2% chance of 40% loss

1.5x Leverage

Hedge option: protects downside below 20% at a price of 1.5% of assets

def portfolio_with_tail_risk(leverage=1.0, tail_hedge=False):

"""Simulate leveraged portfolio with tail risk."""

# Parameters

years = 30

base_return = 0.07

base_vol = 0.15

tail_prob = 0.02 # 2% annual chance

tail_loss = 0.40 # 40% loss in tail event

fixed_costs = 500_000

wealth_paths = []

for _ in range(1000):

wealth = 100_000_000

for year in range(years):

# Normal return with leverage

normal_return = base_return * leverage

normal_vol = base_vol * leverage

year_return = np.random.randn() * normal_vol + normal_return

# Tail event

if np.random.rand() < tail_prob:

year_return = -tail_loss * leverage

if tail_hedge:

# Pay 1.5% for tail protection

hedge_cost = 0.015

if year_return < -0.20:

year_return = -0.20 # Cap losses at 20%

year_return -= hedge_cost

wealth *= (1 + year_return)

wealth -= fixed_costs

wealth = max(0, wealth)

wealth_paths.append(wealth)

return np.array(wealth_paths)

# Compare strategies

unhedged = portfolio_with_tail_risk(leverage=1.5, tail_hedge=False)

hedged = portfolio_with_tail_risk(leverage=1.5, tail_hedge=True)

print("Leveraged Portfolio (1.5x):")

print(f"Without hedge - Median: ${np.median(unhedged):,.0f}; Ruin: {np.mean(unhedged == 0):.1%}")

print(f" With hedge - Median: ${np.median(hedged):,.0f}; Ruin: {np.mean(hedged == 0):.1%}")

Sample Output

Leveraged Portfolio (1.5x):

Without hedge - Median: $551,012,310; Ruin: 0.6%

With hedge - Median: $754,000,522; Ruin: 0.0%

Key Takeaways

Multiplicative processes dominate economics: most financial quantities compound

GBM captures essential features, but real processes have jumps and fat tails

Log-normal distributions arise naturally from multiplicative effects

Path dependence matters: history constrains future possibilities

Geometric mean < Arithmetic mean: volatility drag is real and substantial

Volatility reduction enhances growth: insurance benefit beyond loss coverage

Kelly criterion optimizes growth, providing a natural framework for insurance decisions

Next Steps

Chapter 1: Ergodic Economics - Foundational concepts

Chapter 3: Insurance Mathematics - Specific insurance applications

Chapter 4: Optimization Theory - Mathematical optimization methods